“We need to reclaim the word 'feminism'. We need the word 'feminism' back real bad. When statistics come in saying that only 29% of American women would describe themselves as feminist - and only 42% of British women - I used to think, What do you think feminism IS, ladies? What part of 'liberation for women' is not for you? Is it freedom to vote? The right not to be owned by the man you marry? The campaign for equal pay? 'Vogue' by Madonna? Jeans? Did all that good shit GET ON YOUR NERVES? Or were you just DRUNK AT THE TIME OF THE SURVEY?” ― Caitlin Moran, How to Be a Woman

Feminism has been a contentious word for a while, and many young women seem to associate it, pejoratively, with certain outmoded ideas: man-hating, for instance, or hairy armpits. Women who define themselves as feminists are considered seriously unattractive -- or unattractively serious -- as if they can be conflated into much the same affliction. What is even more troubling, at least to me, is that population of women/girls who think that feminism is no longer necessary because the "battle for equality" has already been won. And yet, so many of the statistics that make up our lives (e.g.,

equal pay,

sexual violence,

rights over our own bodies) suggest otherwise.

In the past year, I've read some really strong

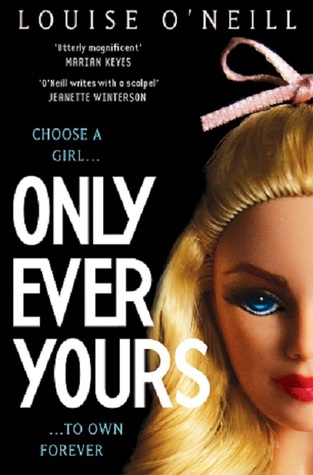

UKYA books that take on feminist issues in ways that are brave, honest, provocative and deeply thoughtful. These books are holding a mirror up to our society and showing us exactly how much work still needs to be done. The word "feminism" certainly never appears in the speculative dystopia that is

Only Ever Yours, but O'Neill gets her message across more than effectively. The mirror she holds up is distorted, definitely, but anyone should feel the horror of recognition of what shows up there.

Am I Normal Yet? takes a more straightforward approach and engages in up-front consciousness raising.

Margaret Atwood's

The Handmaid's Tale was the cautionary tale for my generation of young women seguing into adulthood. Written in 1986, my first year at university, Atwood's influential dystopia imagined a poisoned world where the birth-rate has fallen to an alarmingly low "no replacement" level. Although the true cause of widespread sterility was more to do with chemical warfare, women get scapegoated. The pill, abortions, educated women wanting to work rather than be mothers: all of this dangerous reproductive freedom is held up for blame. And then it is all taken away. Before long, women have no control over their own bodies; if they are fortunate enough to be fertile, they become vessels -- willing or not -- for childbirth

Atwood was writing in a post

Roe v. Wade world, after the first (or arguably the second) wave of feminism. She noted the growing popularity of fundamental Christianity, and her novel served as a warning that hard-won rights for female equality were a slippery slope -- and that it was frighteningly possible to slip backwards.

As I was reading Louise O' Neill's

Only Ever Yours -- which contains such deliberate parallels to Atwood's dystopic vision that it has been marketed as "

A Handmaid's Tale meets

Mean Girls" -- I kept thinking about Atwood's warning to women. In both dystopias, women are reduced and confined to one of three roles: wife/companion, concubine, or chastity/"martha" (in essence, a desexualised cross between a nursemaid and a prison warden). They are a sisterhood which is divided in every possible way and exists only to please and serve men.

Although the creeping religious fundamentalism that Atwood identified has certainly manifested itself, perhaps even more obviously in the Islamic faith than the Christian, the most profound cultural influence of our age has been distinctly secular: the rise of narcissism. Social media, reality television, selfies, You-Tube, the popularity of the

Kardashians, and the list could go on and on. Can anyone under the age of 30, can anyone at all, escape from the picture-taking mirror we keep gazing into? Our smart-phone cameras are mediating our entire existence. The importance of physical appearance, the relentless pursuit of physical perfection and constant self-promotion are our culture's new holy trinity.

Only Ever Yours is a truly frightening book, not only because it imagines what we could could become -- but because it identifies (and satirises) so accurately what we already have become. When the narrator of

Only Ever Yours is punished, her internet privileges are taken away. It is as if her very self is being erased.

"The need to record my life is as fundamental as my need to breathe. Without MyFace, I'm floating. I have nothing to anchor me down, to prove I exist."

In O'Neill's dystopia, women have been genetically engineered to the point that any notion of diversity has been almost entirely lost. As with Barbies, the prototype is exactly the same with slight adjustments in eye, skin and hair colour. Women, who are called "eves" and numbered like prints in the same series, read like a paint chart. Isabel, or rather"isabel", as women are never dignified with capital letters, is described as: PO1 Metallic Silver hair and #76 Folly Green eyes. Although the girls are told that they have been "perfectly designed", they are constantly exhorted to improve themselves. But that quest for improvement is limited, entirely, to physical appearance -- obvious intelligence, or any attempts to cultivate the mind, are discouraged. Curiosity, like anger, is an "unacceptable emotion". Every week the girls are ranked, according to attractiveness, and there is constant competition with no prize at the end. Although they are meant to be happy and positive, they live a goldfish bowl existence of staring at themselves all day and seeing nothing but flaws, magnified. Eating disorders and self-harm, as exemplified by isabel, are the only outlets for mental pain -- and the only ways in which the girls can "own" or control a body that has been created for a man's eventual use.

One of the most painful aspects of the society described in

Only Ever Yours is the way that women are pitted against each other in an endless beauty contest. There is no way for friendship to survive in an atmosphere of constant competition. The

Queen Bee character is called megan, and her cunning manipulations were almost unbearable to read. It was only after I finished the story, and had some distance from it, that I could partly admire megan for the way she utilises personal power in a pretty powerless situation.

Am I Normal Yet? is a very different kind of book from

Only Ever Yours, but in many ways it is examining exactly the same kinds of pressures that are brought to bear on adolescent girls (not to mention grown-up women). Both books show how females mentally flay themselves with negative scripts, especially ones that have to do with being attractive and/or worthy of love. Both books deal with mental illness. Perhaps the major difference between the books -- other than the tone, of course, because one is a dystopia which makes its point through cruel satire while the other is both humorously and earnestly realistic -- is in the portrayal of female friendship.

The protagonist of

Am I Normal Yet? is Evie, a 16 year-old girl who has just started Sixth Form College. Evie is hopeful that a new school will be a fresh start for her, but she is hiding a big secret: she suffers from

Obsessive Compulsive Disorder (OCD) and

Generalised Anxiety Disorder. Evie is on medication and sees a therapist regularly, but she feels constant anxiety about being able to maintain the "illusion" of "being normal". When she makes new friends, specifically Amber and Lottie, she suppresses the truth about what she has suffered:

"mainly because they seemed to like who I was and I didn't want to tarnish the illusion."

One of the big themes in

Am I Normal Yet? is the relationship between the sexes. For Evie, part of being "normal" is being in a romantic relationship -- but she keeps butting up against the harsh reality that teenage boys don't necessarily want the same things as teenage girls do. Evie and her friends set up a feminist support group, which they jokingly refer to as The Spinster Club, but while they discuss a variety of feminist issues, they ruefully acknowledge that the conversation seems to keep veering towards boys and the mixed signals they send. At the beginning of the book, Evie's therapist warns her against relationships with teenage boys:

"they can make you overthink and overanalyse and feel bad about yourself . . . and they can make even the most 'normal' girls feel like they are going crazy."

The girls are pretty clued-up on not relying on boys for their own self-esteem, and yet the progress of the plot makes it clear that being jerked around tends to trigger negative mental scripts -- especially for Evie, who is quite vulnerable to the bad voices in her head. This book is terrific for educating readers about mental illness -- the character of Evie definitely "normalises" her condition by describing its symptoms and treatment in a very relatable way -- but one of the most interesting things it does it connect mental illness with the historical treatment of women. At the end of the novel, Evie makes the point that women are far more likely to suffer from certain types of mental illness -- depression, eating disorders, self-harm -- and that they turn powerlessness inwards.

"I believe the world, our gender roles, and the huge inequality we face every day MAKES US crazy," Evie tells her friends in an impassioned speech at the end of the book.

The female friendships that Evie makes are an important part of her support system; being able to finally confide in Amber and Lottie is part of her growth. The book sends a strong message that female solidarity is of paramount importance to female mental health. If women don't stick up for each other, who else is going to do it?

Only Ever Yours can be found on TRAC's Fantasy reading list and Am I Normal Yet? can be found on TRAC's Overcoming Adversity reading list.

Author Holly Bourne runs The Site, an advice and information forum for young women.