As a parent and educator, I have often thought about the question of how (and when) we introduce the more unpalatable, more disturbing 'stories' from our own human history. I was about 12 when I read The Diary of Anne Frank for the first time, and not much after that, I watched the television series Holocaust. Such cruelty, such kindness, such bravery; such despondency, such hopefulness and sheer determination to live: how do we reconcile those completely opposite human behaviours and feelings? How do we even begin to make sense of them? The vast, complicated story of World War II is one that keeps getting told, and perhaps there are some who would argue that we don't need another book about this historical time period. Personally, I still find the subject fascinating; but I would also argue that in a book as good as this one, the historical background - while obviously not irrelevant - is also not entirely critical for an appreciation of what this author achieves.

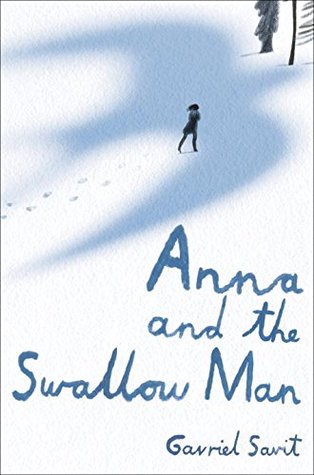

The book begins in Krakow, Poland on November 6, 1939. Anna has just become orphaned, although she doesn't understand that yet. Her father, a linguistics professor, has been rounded up by the Gestapo - along with the other professors in the city. He will not die immediately, but he will disappear from Anna's life forever. Anna is waiting in the street when a tall, thin man appears. He is a man without a name, and a man who wishes to remain anonymous. The man can conjure birds from the sky; Anna is reminded of the wise King Solomon, but Solomon is a bad, dangerous name to have in Poland in 1939. A twisting of the word Solomon, an association with the swallow that alights on her finger, and the tall, thin man becomes Anna's Swallow Man. There is much bird imagery in this book; like birds, the two main characters are constantly migrating - not so much with the seasons, but just to avoid being noticed. Their looping peregrinations through the forests and wetlands of Polands take them nowhere but always away from present danger, and eventually through the years. Their goals are twofold: to avoid capture, and to stay alive.

Both Anna and the Swallow Man speak a number of languages, but the language of "Road" becomes their primary tongue. The language of Road is one of subtle adaptation; Anna learns that you become whichever passport or accent you need to be in order to blend in. Road has different rules; in Road, not telling the truth is not the same as lying. Anna's first lesson is that "people are dangerous. And the more people there are in one place the more dangerous the place becomes." Her second lesson is that "human beings are the best hope in the world of other human beings to survive." Think about how true that is . . . not just in World War II, but at any time.

Savit is certainly not the first writer to use the naive child's perspective as a way of approaching horrors more indirectly, more obliquely. John Boyne's The Boy in the Striped Pyjamas definitely comes to mind; and while some readers love that book, others deplore it for its historical inaccuracies. While Savit employs all of the literary techniques of allegory and analogy - and there are even touches of magical realism - there is something more fundamentally true about his book. Despite its 7 year old protagonist, though, this is not a children's book. I would recommend it for young adults with large vocabularies, a philosophical bent and a tolerance for ambiguity; and that goes for adult readers, too.

Click icon for more

book review blogs

@Barrie Summy

book review blogs

@Barrie Summy