Are you stuck indoors, trying to avoid the whiplash of wind and onslaught of icy rain or even snow?

Well, here is a good tale for a cold winter's day.

In the opening chapters of this historical novel, Little Hawk -- an 11 year old boy of the Pokanoket tribe -- has ventured into the winter woods for his "proving" ceremony.

When my proving time came, snow lay on the round roofs of the homes in our village, and the ground and all the forest trees were white. You were truly a man if you could manage to survive alone, out in the forest, in the darkest part of the year, when most living things on the earth die or sleep, and the cold rules us all. (p. 10)

Author Susan Cooper makes an interesting choice in the lyrical, very otherworldly beginning to her story. Survival, of a single young boy, is reduced to the simplest level. Can he find enough shelter to avoid freezing? Can he find enough food to avoid starving? Can he co-exist with, or if that is not possible, prevail against the other creatures who are also struggling for their survival?

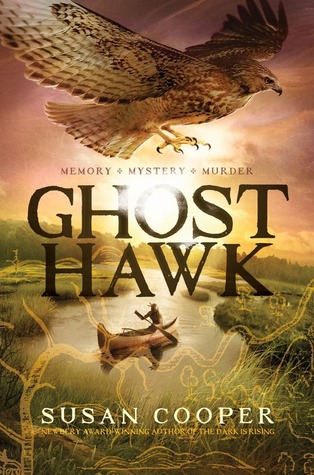

The story begins with an individual -- and then gradually opens up to a wider society: from Little Hawk's village to a wider web of that same tribe, and finally to the commerce and fraught co-existence between the various native tribes of New England (in modern-day Massachusetts and Rhode Island) and the English immigrants. The story gradually progresses from physical survival to the considerably vexed problem of cultural survival, using the braided lives of Little Hawk and an English boy called John Wakeley to tell the tale. The author uses elements of mystery, suspense and surprise to enliven this story of friendship existing within cultural conflict.

Set in the earliest period of colonial America, the book spans the first few decades of the establishment of the Plymouth Colony (1620-40s). There is a sense of slow time versus fast time. Slow time is represented by Little Hawk's tomahawk, which his father made by binding a stone blade between the joined branches of a bitternut hickory tree and then waiting for a decade for the two to fuse inextricably together. Fast time is the same period of time, in which English steel and barrels and disease and land deals are rapidly unravelling the long unchanging existence of the native tribes. The lifespan of Massasoit (also referred to as Sachem and Yellow Feather) also illustrates the swift decline of the Indians in their own native land. From being the saviour of the first "Pilgrims", a friendship which inspired the American holiday of Thanksgiving, to a pragmatic negotiator of peace, Massasoit's accomplishments in diplomacy end with his death. His own son, whose name is Anglicized to King Philip, is remembered for the devastating war which puts the full stop to an experiment in cultural co-existence.

I approached this novel with some misgivings, unsure that a rehashing of the old "Pilgrims and Indians" tale would be of much interest. But as breaking news of jihad in Paris dominates the news, it is really worth examining violence and extremism -- especially as they are promoted under a mantle of religion. Sometimes it is easier to examine these ideas from a historical remove. The experiences of John Wakeley, first in the Plymouth Colony and later in the far more tolerant Rhode Island community founded by Roger Williams, underscore exactly why the separation of church and state was (and continues to be) necessary in the United States. Religious extremism and the cultural racism of "us against them" tend to go hand in hand; against this backdrop, the story points towards another more promising path. This novel has been criticized for not fulfilling, in a narrative sense, the promise of friendship, but sadly that is historically accurate.

Note: You might also enjoy Marcus Sedgwick's review of Ghost Hawk in The Guardian.

Ghost Hawk has been short-listed for the 2014 Carnegie Medal.

No comments:

Post a Comment