Wednesday, 10 May 2017

The Hate U Give

Some people read to find a point of recognition - to find the comfort of their own reality reflected back at them. There are not enough books in which African-Americans feature as the main characters; this is indisputable, it's unfair and it's a problem. For that reason alone, The Hate U Give is a worthwhile book - and yet it is so much more than just a tick on anyone's diversity checklist. Just as importantly, we read to learn about human experiences unlike our own. We read to broaden our perspective. There is nothing quite like reading for developing empathy, and I cannot imagine reading this book without feeling a great deal of that quality for its gutsy narrator and her truly lovable and admirable family. It's a thoughtful, provocative book for sure, but it's also a wonderfully entertaining one.

Angie Thomas tackles a difficult and important subject matter - racism in contemporary America - and she tackles it head-on. At the beginning of the book, Starr and her friend Khalil are pulled over by a policeman as they are leaving a party. The policeman gives no explanation for stopping them, and Khalil makes the mistake of not being obsequious enough - and of not keeping his hands completely and innocently in the policeman's sight line at all times. The policeman makes assumptions first, shoots second, and starts the rationalisations as his third and next move. Meanwhile, a young man has been killed for pretty much no reason at all - except for the fact that he is black, and therefore assumed to be up to no good. Thomas could be lifting this storyline from the newspapers, and indeed, in some ways she is doing just that. There have been some appalling murders of unarmed black men in the US in recent years, and Thomas makes no bones about the fact that she is responding directly to the tragic statistics that have led to the Black Lives Matter movement. Racism comes in all shades and nuances, though, and Thomas is just as adept at illuminating the grayer areas as she is at dark tragedy. 16 year old Starr is a particularly balanced narrator because she straddles two worlds: the 'white' world of her private suburban school and the poor, 'black' world of the urban ghetto where she and her parents have been raised.

Thomas shows, both fairly and realistically, the challenges that poor black communities face. In a Vanity Fair article from November 2013, famous rapper Jay-Z talked about being a drug dealer when he was a young man. Not only does he refer to the 'inescapability' of crack cocaine, but also the fact that drug dealing is the most efficient way out of poverty - at least in the short term. "I was thinking about surviving. I was thinking about improving my situation. I was thinking about buying clothes." Thomas does not shy away from the vexed issue that drugs are for communities like the one that Starr grows up in. Drugs, crime, violence and broken families are all just components of the same problem. Thomas does a terrific job - mostly through the character of Starr's father - of making historical and political connections to the why and how of drugs destroying families and communities. (I would also recommend the documentary Thirteenth, currently showing on Netflix, to any curious and concerned reader of this book.)

I found Starr's voice vibrant and compelling; in my opinion, her story is unputdownable. However, I do know several adult readers who could not get past the urban slang and profanity. What struck me as a strong authentic voice - one that will really appeal to teenagers - does not, perhaps cross over so well to an adult reading audience. I would not recommend this to teens under the age of 14, and I will readily acknowledge that more conservative parents will probably have objections even then. I do believe this, though: this is the world, raw and realistic, that many people have to live in. Ultimately, there is also hope in this story - and that is one of the crucial points which makes it a YA novel. Starr does the right, brave thing and her family is behind her all the way - a wonderful source of strength.

Stacy Nyikos has also reviewed The Hate U Give on her blog Out There

Please visit the Barrie Summy blog for more fresh book reviews.

Labels:

Angie Thomas,

racism,

The Hate U Give

Wednesday, 5 April 2017

Anna and the Swallow Man

As a parent and educator, I have often thought about the question of how (and when) we introduce the more unpalatable, more disturbing 'stories' from our own human history. I was about 12 when I read The Diary of Anne Frank for the first time, and not much after that, I watched the television series Holocaust. Such cruelty, such kindness, such bravery; such despondency, such hopefulness and sheer determination to live: how do we reconcile those completely opposite human behaviours and feelings? How do we even begin to make sense of them? The vast, complicated story of World War II is one that keeps getting told, and perhaps there are some who would argue that we don't need another book about this historical time period. Personally, I still find the subject fascinating; but I would also argue that in a book as good as this one, the historical background - while obviously not irrelevant - is also not entirely critical for an appreciation of what this author achieves.

The book begins in Krakow, Poland on November 6, 1939. Anna has just become orphaned, although she doesn't understand that yet. Her father, a linguistics professor, has been rounded up by the Gestapo - along with the other professors in the city. He will not die immediately, but he will disappear from Anna's life forever. Anna is waiting in the street when a tall, thin man appears. He is a man without a name, and a man who wishes to remain anonymous. The man can conjure birds from the sky; Anna is reminded of the wise King Solomon, but Solomon is a bad, dangerous name to have in Poland in 1939. A twisting of the word Solomon, an association with the swallow that alights on her finger, and the tall, thin man becomes Anna's Swallow Man. There is much bird imagery in this book; like birds, the two main characters are constantly migrating - not so much with the seasons, but just to avoid being noticed. Their looping peregrinations through the forests and wetlands of Polands take them nowhere but always away from present danger, and eventually through the years. Their goals are twofold: to avoid capture, and to stay alive.

Both Anna and the Swallow Man speak a number of languages, but the language of "Road" becomes their primary tongue. The language of Road is one of subtle adaptation; Anna learns that you become whichever passport or accent you need to be in order to blend in. Road has different rules; in Road, not telling the truth is not the same as lying. Anna's first lesson is that "people are dangerous. And the more people there are in one place the more dangerous the place becomes." Her second lesson is that "human beings are the best hope in the world of other human beings to survive." Think about how true that is . . . not just in World War II, but at any time.

Savit is certainly not the first writer to use the naive child's perspective as a way of approaching horrors more indirectly, more obliquely. John Boyne's The Boy in the Striped Pyjamas definitely comes to mind; and while some readers love that book, others deplore it for its historical inaccuracies. While Savit employs all of the literary techniques of allegory and analogy - and there are even touches of magical realism - there is something more fundamentally true about his book. Despite its 7 year old protagonist, though, this is not a children's book. I would recommend it for young adults with large vocabularies, a philosophical bent and a tolerance for ambiguity; and that goes for adult readers, too.

Click icon for more

book review blogs

@Barrie Summy

book review blogs

@Barrie Summy

Tuesday, 3 January 2017

The Secret of Nightingale Wood

This is a children's book suitable for all ages, but probably best appreciated by adults who are still love with their childhood favourites: The Secret Garden, A Little Princess, The Wind in the Willows, Alice in Wonderland and fairy tales of all descriptions. Author Lucy Strange deliberately borrows some of the tropes from the best-loved classics, but fashions them into something original. Set just after World War I, the story explores madness and loss - and the sometimes fine line between fantasy and reality. Mental health is very fashionable in children's and YA literature right now, but Strange (such an apt name) very much suits her themes to her era. The rather brutish and patriarchal attempts to deal with shell-shock and the depression brought on by profound grief are a powerful, dark spectre in this book. Sometimes what is lurking in the woods is ominous . . . and sometimes it is just sad and lonely. The influence of fairy tales is quite strong in this book. And as in all the best childhood classics, it takes a brave, resourceful child to heal the broken world. I did worry, at first, that there was something too perfect and paint-by-number about this book, but I was completely won over by the ending.

The protagonist of the book - Henrietta, called "Henry" - is having to cope with way too much trauma. Her older brother has died in a tragic accident; her mother has retreated into a drug-addled depression; her father is permanently away on business; and a creepy, ominous doctor is trying to make decisions for the family which Henry instinctively feels are wrong. Henry copes by turning to her beloved stories. They are her companions in loneliness, but they also offer safety, comfort and even guidance as she tries to navigate the difficulties of her life. The thing for Henry, though, is figuring out the difference between inspired by stories - and potentially being misled by them. The author has a very deft way of guiding Henry through her own imaginative thicket. This extremely accomplished first novel definitely has a touch of magic in it.

"Mama was quiet for a moment and then she said, 'What a wonderful place the world would be, Hen, if everyone had your imagination.'"

The protagonist of the book - Henrietta, called "Henry" - is having to cope with way too much trauma. Her older brother has died in a tragic accident; her mother has retreated into a drug-addled depression; her father is permanently away on business; and a creepy, ominous doctor is trying to make decisions for the family which Henry instinctively feels are wrong. Henry copes by turning to her beloved stories. They are her companions in loneliness, but they also offer safety, comfort and even guidance as she tries to navigate the difficulties of her life. The thing for Henry, though, is figuring out the difference between inspired by stories - and potentially being misled by them. The author has a very deft way of guiding Henry through her own imaginative thicket. This extremely accomplished first novel definitely has a touch of magic in it.

"Mama was quiet for a moment and then she said, 'What a wonderful place the world would be, Hen, if everyone had your imagination.'"

Wednesday, 2 November 2016

Asking for It

I "recommend" this book to you with many reservations; perhaps it is more accurate to say that I bring it to your attention rather than actually recommend it. I disliked this book from the beginning, and found it to be an emotionally gruelling read in every sense. I felt completely wrung out by the ending, and I couldn't sleep for thinking about it. I cannot say that it has any literary qualities, either, unless you count a brutal realism. I do not think it reflects the reality of all 18 year olds - which is the age of protagonist Emma O' Donovan - but I suspect it will be realistic for many young adults. Yes, this book is deeply disturbing; but then so is the issue that it is unflinchingly describes.

Other Young Adult books have tackled the subject of rape - Laurie Halse Anderson's Speak comes to mind - but I don't think any book has been brave enough to set up its victim in every possible way, and still bring home its point. The really provocative thing that Irish author Louise O'Neill does is create an unsympathetic protagonist, and then demonstrate that no woman or young girl deserves her fate. Emma O' Donovan is the town beauty - the town being Ballinatoon, Ireland - who has traded on her beauty all her life. She is vain and superficial; she doesn't treat her friends particularly well; and she enjoys the power over boys/men that her face and figure give her. Listening to Emma's internal dialogue was like fingernails on a chalkboard for me (ie, deeply grating). But even at her most unlikeable, Emma is still only 18, and still insecure and vulnerable at her core. Her beauty is a double-edged sword after all, and that she fears that no one - not even her mother - sees her as having any other value.

So Emma goes to a party: she dresses provocatively, she drinks too much on an empty stomach, she takes drugs in order to appear cool, she flirts with a man, not because she is really attracted to him, but because she wants to make someone else jealous, and she loses control of the situation. What happens next is clear-cut rape, and yet almost no one - including Emma - wants to call it what it is. This story is one big set-up of "blaming the victim," and the author is quite adroit at showing the reader why we still do blame the victim in what is supposed to be a more enlightened, less mysogonistic age. Social media plays a role, too, and Emma is further humiliated and victimised by Facebook. Her case then becomes a "cause celebre" in Ireland, and her privacy is violated again and again.

For much of the novel, Emma is too immersed in her own sense of shame and humiliation to even feel righteously angry on her own behalf. As much as I disliked this novel, I do admire the author's bravery and willingness to draw attention to a deeply rooted cultural problem. Sexual assaults and rapes are rarely prosecuted, or even reported, and female victims are still very likely to be blamed - and to blame themselves. This book is deeply discomfiting, but it is thought-provoking, too - and will probably be eye-opening for those who undergo the ordeal of reading it.

Click icon for more

book review blogs

@Barrie Summy

book review blogs

@Barrie Summy

Wednesday, 5 October 2016

A Court of Mist and Fury

When my daughter was a young teenager, we discovered the novels of Robin McKinley together. McKinley won the Newbery Medal for The Hero and the Crown in 1985, and has been specialising in a particular kind of fantasy novel ever since. Most of her novels (20+) are inspired by fairy tales, but with a notably feminist slant: a young woman is always the heroic figure at the heart of the story. When done well, this is a formula that my daughter is guaranteed to love - so I am always seeking out new titles which have these same characteristics. In the past year, I have had some notable successes: first, with Uprooted by Naomi Novik, and then most recently with Sarah J. Maas's "A Court of Thorns and Roses" trilogy.

Sarah J. Maas has gained a huge fan base with her Throne of Glass series, and her latest series incorporates many of the same ingredients. You could argue that they are coming-of-age books in which a young girl - isolated in a variety of ways - is given much in the way of natural (and magical) gifts, but then much is asked of her. She must grow in strength, and fight through a world of evil in order to rule. And as we all know, it's not easy being Queen.

A Court of Thorns and Roses begins with the familiar outline of the Beauty and the Beast fairy tale: three sisters, a merchant father who has lost his fleet and fortune, a desperate bargain, a dark curse. Feyre is the youngest of three daughters, but the only one who has the strength to go out into the cold, dense forest and hunt for her family's supper. When she kills an animal who turns out to be High Fae in disguise, a dreadful lion-like beast turns up in a rage and claims Feyre as his recompense. She must accompany him to his kingdom, on the other side of a Wall that separates human and the Fae (ie, faeries), or have his vengeance turned on her entire family. Like most good fairy tales, this one begins with a sacrifice.

So far, so familiar . . . but Feyre's story quickly develops into something unexpected, something that draws upon both the old and the new in terms of magic and folklore. Feyre brings her human qualities (notably her strength, stubbornness and loyalty) into a situation where nothing (neither creatures nor landscape) is at all what it seems. And unlike the original fairy tale, love alone will not break the spell. Feyre has to undergo trials which the original Beauty couldn't have imagined, much less endured, and there is adventure, violence and a touch of the macabre in the book. There is also some strong language and some sexual scenes, which firmly place the series in the upper reaches of YA (Young Adult) fiction - or what some people are now describing as "New Adult." This is not your children's fairy tale, likely to show up in a Disneyfied animation. There are fairies, yes, but they are complicated creatures.

A Court of Mist and Fury is the second book in the series, and I am not alone in thinking that it is a great improvement over the first book. Feyre still possesses a human heart and understanding, but her body has become magical and eternal. Rhysand, the High Lord of the Night Court, was both adversary and unexpected ally in the first novel, but Feyre's relationship with him will be transformed in this second instalment to the series. I don't usually look for life lessons in fantasy novels, but Mass does something very interesting with the two lead male characters in this series. There is a world of difference in the way that Tamlin (the Beast) and Rhysand treat Feyre, and it forces the reader to consider her own expectations regarding romantic relationships. There is emotionally satisfying romance in this series, but it is always secondary to the adventure - and even more importantly, the growth of the central female character.

My daughter has reached an age in which we can enjoy the same books, and we are both eagerly awaiting the third instalment in this exciting series.

Click icon for more

book review blogs

@Barrie Summy

book review blogs

@Barrie Summy

Wednesday, 6 April 2016

Illuminae

Does this book cover draw you in or put you off?

I'm a big believer in the importance of reading outside of your comfort zone . . . not all the time, but certainly once in a while. Although I've enjoyed some science fiction books, sci-fi is definitely not the first genre I'm drawn to. I was never that kid watching Star Trek. But sometimes, it really is invigorating to be shaken out of one's comfortable reading groove.

It's difficult to categorize either the plot or the appeal of Illuminae, but I'm pretty sure that most reviewers will resort to the word 'original' at some point. It combines a science fiction technology and time-frame with a post apocalyptic virus run amok . . . not to mention an operating system with a God complex. There are war games, mysteries galore, paranoia to spare, and incredibly creative graphic elements that piece the story together. Usually graphic novels are easier to read than traditional prose, but not this one. It reminded me that science fiction reading preferences are definitely associated with high IQs. I struggled to follow all of the technical bits -- which is where the average computer-savvy 17 year old will probably be way ahead of me -- but the romance, suspense and humour were strong enough to keep me engaged as a reader. The main characters, on-off couple Kady (a gifted hacker) and Ezra (athlete turned fighter pilot), are strong, smart, brave and quick with the witty IM banter.

Definitely recommended for older teens, especially the hard to please male contingent, anyone who likes science fiction and those readers who want to try something really 2575.

Click icon for more

book review blogs

@Barrie Summy

book review blogs

@Barrie Summy

Wednesday, 2 March 2016

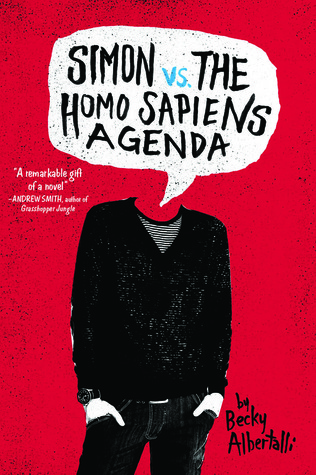

Simon vs. The Homo Sapiens Agenda

The problem with reading book summaries is that they often focus on some aspect of the plot that might seem "gimmicky" (at least to this reader), and that can put me off. Neither the title nor the "hook" of this book encouraged me to read it, despite the almost universal acclaim. If you have been similarly disinclined, let me reassure you: this book is a must-read for fans of contemporary Young Adult literature. It is frank, funny, warm and has such a great voice. Author Becky Albertalli is a clinical psychologist who works with teenagers, and her love and respect for her subject shines through every aspect of this book.

The plot kicks off with 16 year-old Simon Spier engaging in a highly secretive email exchange with another boy in his school. Through the freedom of an anonymous email account, Simon (aka Jacques) is exploring the possibility that he might be, probably is in fact, gay. Neither Simon nor his confidante "Blue" is ready to come out, even to each other, but their email confidences gradually deepen into a relationship which is important to both of them. So here's the rub, and nub of the plot: Simon gets busted by Martin, an acquaintance in his drama group. Martin proposes a deal (ie, blackmail): He will keep Simon's secret, as long as Simon champions his courtship of Abby (an alpha female who happens to be one of Simon's best friends). Although Simon's "coming out" is the central drama of the plot-line, the book is exceptionally strong on friendship. For most people in this age group, friendships are far more important than romantic relationships -- and this is underscored over and over again through Simon's bumpy progress towards romantic happiness.

There were was so much to admire in this book, but I particularly appreciated the active presence of loving parents. There are so many examples of dysfunctional or completely absent parents in YA literature; sadly, it is almost a novelty to find a positive (yet realistically so) parent-child relationship. Probably the worst thing about Simon's father, in particular, is that he makes the common mistake of being tragically "hip". Not only does this result in tasteless jokes, but it also defies that generational law: Thou Shalt Not be Hipper Than Thy Teenager. Even teenagers from close families need their emotional space, and I haven't met a teenager yet who wants to discuss his or her sex life with parents. One of the funniest lines in the book, at least for me, was Simon's rueful acknowledgement that his parents' eager desire to "share" with their children could be "more exhausting than keeping a blog."

We still live in a world where most parents, no matter how liberal and loving, will have a bit of an emotional adjustment period at the revelation that their child is gay -- if only because of worry for the greater difficulties that their child may face. One of the things that Albertalli gets exactly right is that she creates something close to a best-case scenario -- good friends, supportive parents -- and then she acknowledges that "coming out" is still a difficult thing. The truly genius thing about this book, though, is that it is so much more than a coming out story of one boy. Simon knows his parents will accept his sexuality with grace; the thing that really worries him is the scrutiny. Adolescence is a time of great flux -- of figuring out how you are -- and that can be both tiring and painful. As Simon puts it:

All I ever do is come out. I try not to change, but I keep changing in all these tiny ways. I get a girlfriend. I have a beer. And every freaking time, I have to introduce myself to the universe all over again.

Click icon for more

book review blogs

@Barrie Summy

This book appears on TRAC's First Love reading list. Please visit the TRAC website for more details about the Teen Reading Action Campaign.

book review blogs

@Barrie Summy

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)